The following essay appeared in the summer 2019 issue of Scalawag Magazine, and made the 2019 list of top Scalawag picks. It is available on the magazine’s website upon activating a free membership to Scalawag.

Learn more about the Kingdom of the Happy Land from Henderson county librarian and storyteller, Ronnie Pepper. Click here for an interview with Ronnie about Appalachia’s whitewashed past (2020), and scroll to the bottom to hear Ronnie re-tell the Kingdom’s story (2019).

Editorial note: In the original version, I misused the Cherokee term ᏣᎳᎩ (Tsalagi) the name of the Cherokee language. What should have appeared, and what I’ve used here is ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯ (Aniyunwiya), which means “The Principle People” and what the Cherokee have called themselves. This updated version also includes additional images from Buncombe County Special Collections and The Cherokee One Feather.

A Black kingdom in postbellum Appalachia

Growing up in the Blue Ridge Mountains of western North Carolina, I was taught to see the region as part of who I was: a white person from the Mountain South. I learned from the nearby national parks and the public school system that our local history was one of white settlement and sharecropping, natural conservation and tourism. The Mountain South I was raised in, and that raised me, taught me that the mountains offered freedoms to white people caught in the doldrums of wage labor. We could hike and camp and fish and tube on rivers—and now drink local craft beer—to participate in the pleasures of the mountains.

But like all white settler fantasies, this white mountain tale hides a complex history of layered dispossessions and diverse populations. The ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯ (Aniyunwiya; “The Principle People” or Cherokee) have called the Mountain South home for thousands of years. White settlers brought enslaved people of African descent here. Other Black families arrived in the mountains of Southern and Central Appalachia after the Civil War to work on farms or in coal fields, respectively. More recently, in the latter half of the 20th century, migrant workers from Mexico and Central America moved to the mountains as agricultural laborers along with other populations from the global South, such as Southeast Asia.

As I've grown older, I've come to recognize that many white people, those raised in the region and not, are reproducing a singular history of white settler place-making in Southern Appalachia. To indulge in an illusion of a homogeneous white geography has harmful consequences. Namely, it erases the histories of Native and Black and brown people who live in the mountains of Western North Carolina and beyond. When white people overlook the past and present of Appalachia's diverse communities, we facilitate the rapid displacement of Native, Black, and brown peoples to make way for more economies of pleasure based on white settler visions of mountain leisure. In other words, if we cannot imagine Native and Black and brown people living in the Appalachian Mountains, it is because we have ignored their histories and their present-day lives, and thus we aid the foreclosure of their futures here.

In Western North Carolina, Black community organizers and scholars work hard to preserve Black Appalachian histories to create Black Appalachian futures. One of those histories was hidden in my own community—The Kingdom of the Happy Land.

The Kingdom of the Happy Land was a Black communal society in Western North Carolina during Reconstruction. Nestled in the valleys and ridges along Lake Summit near the small town of Tuxedo, North Carolina, The Kingdom embodied a larger history of Black, rural place-making and an early vision for Black settlement in the southern mountains. But the history of The Kingdom is not well known. The material remains of The Kingdom and living memories of it have all but vanished. Whispers of it appear irregularly in local news articles to reflect on the curious story of a Black Appalachian utopia. But The Kingdom's structures have toppled, some from rot and others from intentional removal.

In the Appalachian tradition of speaking back, I hope I have made clear: Appalachia has never been all white. Many peoples have intimate connections to its mountain landscape.

Throughout my entire education in the Henderson County Public Schools system in Western North Carolina, as a camper and worker at a Camp Green Cove whose land crisscrosses the boundaries of The Kingdom, and as a person with ties to Lake Summit and Tuxedo, I never learned the history of The Kingdom. Yet, I spent years and years of my childhood playing in the hillsides that provided refuge for generations of freedpeople over a century ago, all the while being taught white-only representations of Appalachia.

In the summer of 2018, I returned to Western North Carolina for my dissertation research exactly one decade after I'd left home to pursue a career in New York City (young people from Appalachia are often encouraged to seek opportunities elsewhere). Now, as a graduate student at UNC-Chapel Hill, I am working on a project about race and reproductive justice in Southern Appalachia. During my research into those topics that I stumbled upon The Kingdom in Phoebe Ann Pollit's book, African American and Cherokee Nurses in Appalachia. Bewildered, I raised The Kingdom to a new friend of mine, Phyllis Utley. Phyllis calls Western North Carolina home. She is a social justice organizer, an educator, and a member of the City-County African American Historical Commission in Asheville. Phyllis knew the history of The Kingdom well. She learned about it at a play produced by local storyteller Ronnie Pepper for Black History Month at a Henderson County high school. When we spoke about The Kingdom, Phyllis told me her plan to create a children's book about The Kingdom with activities for children to imagine their own visions for a better world, a nod to the visionary Black leaders of The Kingdom who built their own Black place in the Mountain South.

The history of The Kingdom of the Happy Land

In the years of anti-Black terror that unfolded in the wake of the U.S. Civil War, a group of freedpeople abandoned the place where they were enslaved in Mississippi and ventured into the nearby foothills of the Appalachian mountains in northeastern Alabama, walking north along the peaks and valleys in search of utopia. From Alabama to Georgia to South Carolina, dozens more freedpeople joined this collective march into the Mountain South.

"Follow me and I will lead you to The Kingdom… We are going to the Happy Land," proselytized Robert Montgomery, the soon-to-be king of the Black mountain utopia, according to one account.

Several sources locate The Kingdom's origin in 1866 when approximately 50 freedpeople traversed the mountains from the Deep South to a small mountaintop in Western North Carolina—the same year white supremacists established the Klu Klux Klan in nearby Tennessee while southern states passed the Black Codes to restrict freedom from the newly liberated Black American population. Over the next few years, The Kingdom is believed to have grown to a 200-person communal society with a king and a queen and a common treasury. The inhabitants were subsistence farmers and procurers of herbal liniments, namely a rheumatism treatment called Happy Land Liniment, which they sold in nearby towns like Hendersonville. Earnings from the liniment, harvested produce, and the freedpeople's outsourced domestic labor were deposited in the common treasury with the intention of purchasing the land they had established as their visionary settlement. Land ownership for Black Americans in the Reconstruction era secured freedom from sharecropping and other forms of labor theft that continued in the afterlife of American slavery. In 1889, Robert Montgomery purchased a tract of land from Septa Davis, the owner of a local inn.

The Kingdom is believed to have grown to a 200 person communal society which included a king and a queen and a common treasury. The inhabitants were subsistence farmers and procurers of herbal liniments, namely a rheumatism treatment called Happy Land Liniment, which they sold in nearby towns like Hendersonville, North Carolina.

Few historical records exist that help trace the history of The Kingdom. And without a written record, many of the discrepancies become hard to parse.

According to some source material, such as a thin book published by Sadie Smathers Patton titled, The Kingdom of the Happy Land, the communal society reigned for roughly 50 years, from the 1860s to the 1910s.

Across historical accounts, The Kingdom's origins vary. One account traces a formerly enslaved man from Mississippi named Robert Montgomery who gathered freedpeople across the South and journeyed north toward a utopia. The destination, an inn called Oakland, was known to some freedpeople because plantation owners from the Deep South vacationed in nearby Flat Rock. Oakland was on the Buncombe Turnpike between Greenville, South Carolina, and Asheville, North Carolina. The widowed owner of Oakland, Septa Davis, is alleged to have allowed the freedpeople to take residence on the land in exchange for labor at the inn. This account claims Robert married a freedwoman named Luella, a healing woman and educator, and together they reigned as king and queen of The Kingdom.

Another account claims a man, whose father was a plantation owner and whose mother was an enslaved woman, moved his enslaved people, now freedpeople, north seeking a freer and safer place to live. In this version, Robert and Luella are not the founders but arrive later as in-laws.

All the sources make clear that Robert Montgomery and Luella, no matter their relation, were king and queen of the Kingdom of the Happy Land. All sources also confirm a communal society that valued spirituality, education, and wellbeing. But these diverse accounts of The Kingdom only raise more open-ended questions: What did it mean for a communal utopian society to have a king and queen? How was power imagined and distributed? Who controlled the common treasury?

The rhododendron blanketed mountains—where the freedpeople found sanctuary in their vision of a Emancipation era utopia—conceal this history. After the king and queen of The Kingdom passed away, and members of the Kingdom inherited the responsibilities of the utopia, its visionary promises began to fade and families moved away to nearby Flat Rock or deeper into the mountains in Sylva, or they departed southbound toward the Appalachian foothills near Spartanburg, South Carolina. Over the next century, the cabins built by the freedpeople decayed and turned to dirt while the earthen cellars collapsed and disappeared into the landscape. By the early 2000s, only tumbled stone chimneys indicated the abandoned vision for Black world-making in Southern Appalachia.

That the freedpeople found their utopia in Western North Carolina comes as little surprise to me. These mountains, part of one of the oldest mountain chains in the world, have been a cherished place since time immemorial.

In these mountains exists the Kituwah Mound, the ancestral mother town of the ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯ (Aniyunwiya; Cherokee). According to Cherokee scholar and enrolled ᏣᎳᎩᎯ ᎠᏰᎵ (Tsalagihi Ayeli; Cherokee Nation) member Tom Belt, "The boundaries of Kituwah aren't confined to the area. It's intrinsic to the heart and soul of the Cherokee people… This is the heart of the Cherokee world. All of our stories began here, where we began as people."

Not 30 miles south, the freedpeople found their own place for worldmaking. But four decades before The Kingdom's founding, the U.S. government had violently removed many of the ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯ (Aniyunwiya; Cherokee). Many of us know this as the infamous anti-Indigenous and genocidal project, the Indian Removal Act. Some ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯ (Aniyunwiya; Cherokee) found refuge in the mountains and remained; they are the ancestors of the ᏣᎳᎩᏱ ᏕᏣᏓᏂᎸᎩ (Tsalagiyi Detsadanilvgi; Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians).

More recently, Western North Carolina has become a home to a large Latinx population, one of the largest Latinx populations in the state, who labor in the agricultural and tourism industries that sustain the local economies.

In the Appalachian tradition of speaking back, I hope I have made clear: Appalachia has never been all white. Many peoples have intimate connections to its mountain landscape.

Black Appalachia in Western North Carolina Today

During my research in fall 2018, I returned to Lake Summit to try and locate The Kingdom based on descriptions I read in local newspapers. Instead I found hostile trespass signs and tripwires.

Today, a marijuana cannabidiol (CBD) farm using The Kingdom's namesake, Kingdom Harvest, claims the land where not a single historic marker acknowledges the significance of the place's past. I contacted affiliates of the summer camp, who once used the land where The Kingdom reigned, to learn about the new owners. According to the affiliate, the new owners had revoked all permissions to visit The Kingdom. The camp affiliate did not know of any plans to designate The Kingdom as a historical site.

That Kingdom Harvest would use the name of a historic Black Appalachian community and not preserve that history, at the least, is theft. In the words of William H. Turner, a leading scholar on Black Appalachia, "They're taking our stuff."

There is a violent irony that the site of a historic Black commune is now a private cannabis farm, an industry that profits from the legal sale of a substance that claims many Black lives in the United States carceral system. Data from the American Civil Liberties Union indicates that Black people in America, who use marijuana at the same rate as white people, are arrested at four times the rate of white people for marijuana possession. Once in the U.S. carceral system on drug charges, human life becomes a source of extracted labor that is maintained through draconian sentences, high bail fees, and permanent criminal records. Meanwhile, the hemp and CBD market, dominated by white "entrepreneurs," was valued at $591 million in 2018.

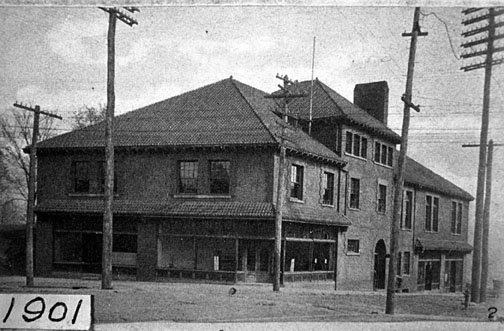

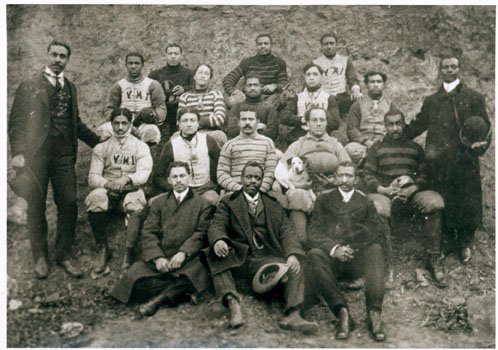

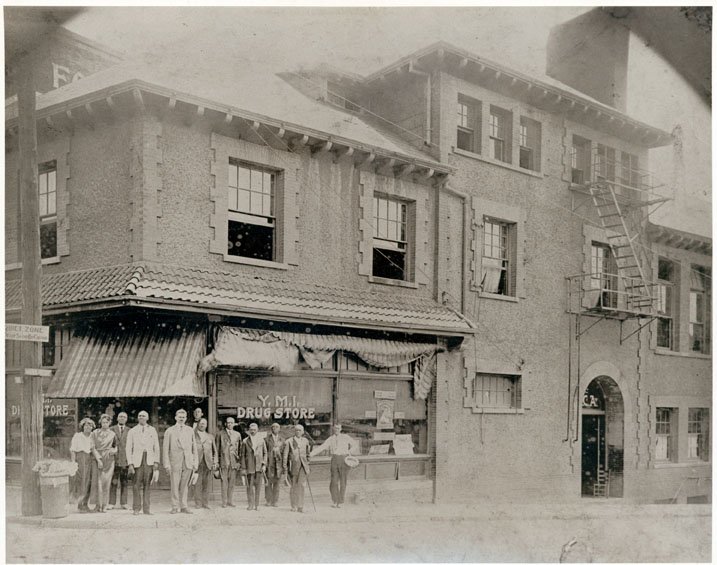

That Kingdom Harvest would use the name of a historic Black Appalachian community and not preserve that history, at the least, is theft. In the words of William H. Turner, a leading scholar on Black Appalachia, "They're taking our stuff." When Turner delivered the keynote lecture for the 2019 African Americans in Western North Carolina and Southern Appalachia Conference at the historic Young Men's Institute Building in downtown Asheville, he denounced the erasure and appropriation of Black histories in Appalachia.

"People need a past," he said.

The Kingdom of the Happy Land is an important historic moment in a long arc of Black place-making in the Blue Ridge Mountains of Western North Carolina. That is why we must not forget it.

The Young Men's Institute Building, built in 1893, belonged to a vibrant Black corridor of town. Once segregated, Eagle Street and Market Street, where the Building sits, has since slowly filled with the same sterile storefronts and generic apartment buildings that are suffocating downtowns in cities across America. As Keynon Lake, creator of My Daddy Taught Me That and recipient of the Community Award at the Conference, noted, "We are sitting in the second oldest Black building in the nation in the number two city for gentrification."

"They are taking our stuff."

Just as it is important to save the history of Black Appalachia, so too is it important to make Black history in Appalachia. Scholars like Karida Brown, Jillean McCommons, Cynthia Greenlee, Crystal Wilkinson, bell hooks, Adam McNeil, Darin Waters, Dwight Mullen, William H. Turner, and the recently passed Ed Cabbell—as well as community educators like Ronnie Pepper and Phyllis Utley—have helped me understand that Black history supports Black futures. The Kingdom of the Happy Land is an important historic moment in a long arc of Black place-making in the Blue Ridge Mountains of Western North Carolina. That is why we must not forget it. And we must also not forget that Black communities across the region are doing critical work today to advocate for their health, their homes, their children, their families, their neighborhoods, the Affrilachian artist movement, and so much more. There remains much more to be done to make that work visible, valued, and supported.

Below are some of the Black-led spaces and organizations in Western North Carolina you can support.

African Americans in Western North Carolina and Southern Appalachia Conference

Arthur R. Edington Education & Career Center

CoThinkk

Hood Huggers International

My Community Matters

My Daddy Taught Me That

My Sistah Taught Me That

Pigeon Community Multicultural Development Center

Sistas Caring 4 Sistas

Southside Rising for Justice

Stephens-Lee Recreation Center

One Dozen Who Care

Word on the Street

Youth Transformed for Life (YTL)

Special thanks to Theda Perdue, Phoebe Pollitt, and Phyllis Utley for their generosity and expertise as I stumbled onto The Kingdom. And to my father who taught me there is so much to learn from the mountains.

Ronnie Pepper tells the story of the Kingdom of the Happy Land for the Historic Saluda Committee’s Step Back in History program, October 2019.